Moral Kiosk

Reading Log, Summer 2022

Girls They Write Songs About, by Carlene Bauer.

Mrs. Bridge, by Evan S. Connell. This affecting but limited novel, first published in 1959, remains something of a cult favorite for a certain stripe of soi disant writer’s writer. The titular protagonist is a Kansas City matron of aggressive ordinariness, the banality of whose life is sketched in a long series of brief, cryptically titled chapterettes. This mildly experimental device works surprisingly well, but the book lacks the transcendent consciousness of a Joyce or Woolf — two authors whose subjects were the quotidian and the banausic. It has instead a whiff of mid-century social realism, as exemplified by Upton Sinclair, among others — emphatically middlebrow, in Dwight Macdonald’s famous formulation.

“The Rich Boy”; “Winter Dreams,” by F. Scott Fitzgerald. I have been re-reading these stories for half of my life, and I still don’t quite understand the source of their durable allure. In some ways, they present Fitzgerald at his worst: soppy, starry-eyed, emotionally adolescent, an overt elitist and valorizor of shallow values; “Winter Dreams” also contains this priceless line, spoken apparently without irony by the female love-object: “I’m more beautiful than anyone else, why can’t I be happy?” Despite such howlers the stories have a charm that I cannot resist. They also are interesting because they play out, imperfectly and in miniature, the themes and motifs that were to find such sublime expression in The Great Gatsby — literally a perfect novel — and it is interesting to trace this development. Reading them is like listening to an early demo of a great, much-loved song: you can see its qualities in embryonic form.

The Man Who Saw Everything, by Deborah Levy. Cunning, cerebral, more than a little sinister, this novel operates at a level a notch or a notch and a half below masterpiece, which is to say, at a very high level indeed. Levy’s protagonist is Saul Adler, a young English historian who goes to East Berlin in 1988 — just before the fall of the Wall — to do research on an abstruse branch of German history. The prose has a dry, precise tone, a little dull, but spiked by touches of the surreal. In its second half, however, the story picks up twenty-eight years later, and its grip immediately becomes magnetically strong. To break a novel in half and revisit its first part from multiple perspectives of the second half’s vantage is not exactly a new trick, but I have never seen it handled so beautifully as it is here. The intricate structure of intersecting timelines Levy has built click into place with chilling assurance, and the result is both emotionally satisfying and draining.

Socialist Realism, by Trisha Low. Not what it says on the tin. It seems to me that the two signature genres of our etiolated time are auto-fiction and auto-theory, not coincidentally both styles of writing that are aggressively reflexive. Since I am disgusted with and bored by contemporary fiction and poetry, and have no use whatever for big-men-of-history-type tomes, I am almost by process of elimination left with auto-theory, a sub-genre of book that kicked into gear with the publication, in 2015, of Maggie Nelson’s coruscating The Argonauts. This was something genuinely new: a smart, free-wheeling hybrid of memoir, gender theory, art writing, and literary criticism, unconstrained by category or formula. Since then, the template has been copied repeatedly and with highly variable results.

This is, of course, as it should be; any new angle or approach testifies to the continued vitality and potential of nonfiction writing. Nonetheless, at times while reading Trisha Low’s book I had the sneaking feeling that I was witnessing the principle of diminishing returns in action. Low’s book hops from topic to topic, circling the unanswerable question what is art for? — the title is not completely misleading — with a great deal of intelligence and style, but it also seems at times slightly forced, even performative. The wrinkle here is a narrow but unmistakable reactionary streak, as when the author voices irritation with the politics of trauma as cultural narrative. Not maybe the best look for someone who elsewhere records the mechanics of purchasing a $25,000 handbag.

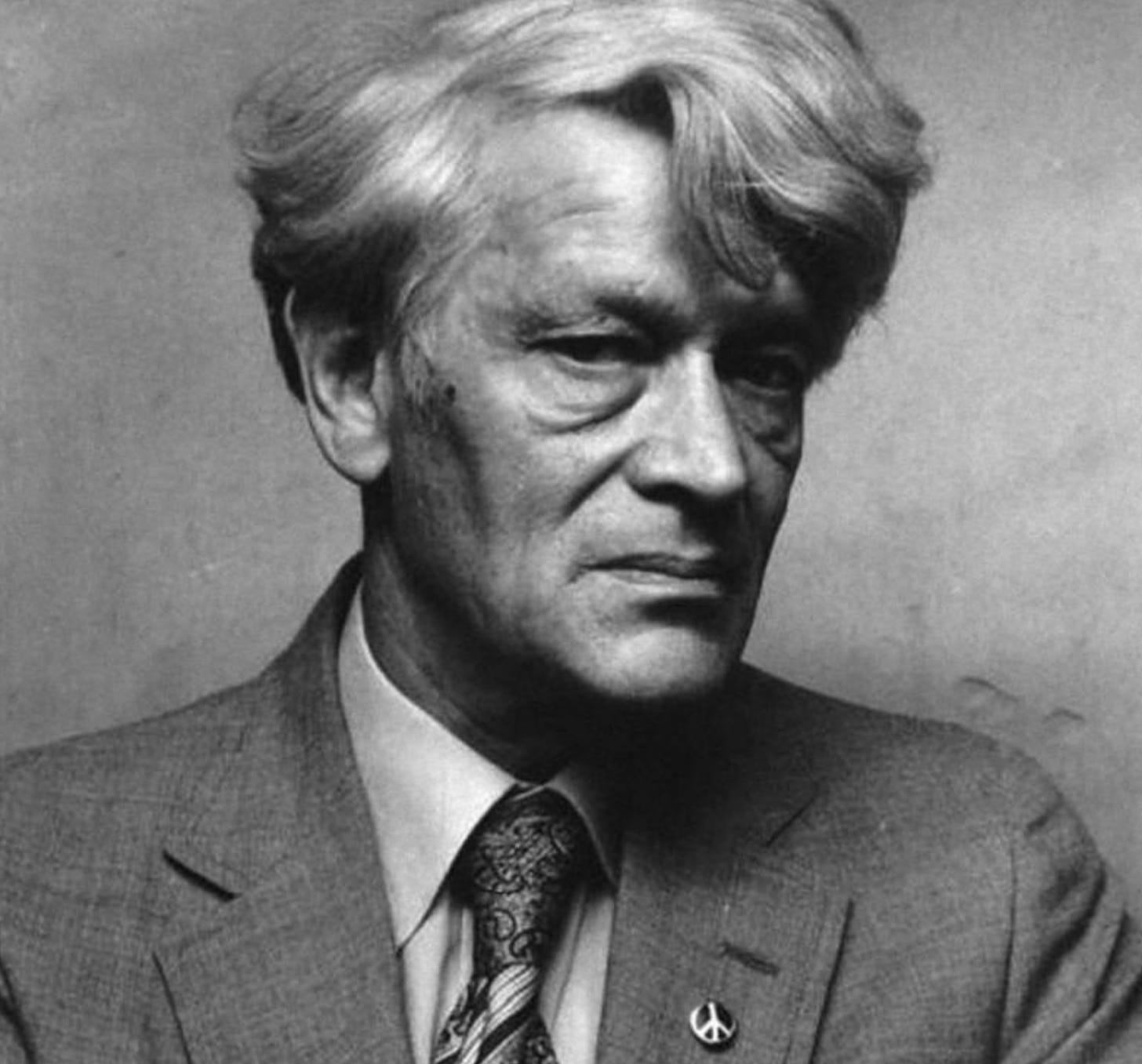

“Labor, Time-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism,” by E. P. Thompson. The late Thompson is one of those cultural theorists one has heard about all one’s life, so it was overdue and refreshing to read this classic essay, which sets forth a crisp thesis about the monetization of time by capitalism at its most basic level, in very accessible, if heavily footnoted, language.