Practice, by Rosalind Brown. This chilly, elegant debut novel by a young British writer gradually accumulates a mesmerizing psychic momentum that eventually transforms into a hypnotic literary experience. In Woolfean high modernist mode Practice inhabits the consciousness of an undergraduate scholar at Oxford over the course of a moderately uneventful day, but Brown’s command of the language and almost supernatural ability to summon the delicate tendrils of interior thought make for a transcendent experience. Brown’s protagonist is a spare, cerebral yet sensuous young student with terrifying command of her mind and body; she has the affect of a nun poised in sacerdotal silence, except that she also lapses intermittently into erotic reveries of disconcerting intensity. The author’s ability to limn the ethereal traces of a mind focused intently on literature — Annabel is writing a paper about Shakespeare’s sonnets — is extraordinary:

She flips to another sonnet at random. You are all the word, and I must strive To know my shames and praises from your tongue. Yes it’s there: a sort of baldness in the tone, plaintive, and domineering … how he insists again and again on his own enslavement while remaining absolutely in charge.

The melding of the object of study and the train of thought, the sense almost of inhabiting the rhythms and channels of a mind long dead; these are experiences that are almost impossible to capture, and yet Brown does it continually. A remarkable achievement. Postscript: I have since learned that Practice stands as an example of “the literature of attention,” the newest sub-sub-genre of fiction, which continues to subdivide itself into ever narrower channels and rivulets.

Revelations, by Judy Chicago. There is something absurd about me, Mike Lindgren, pronouncing an opinion about this capstone document of a famous feminist artist’s career. Nonetheless, I clear my throat timidly and say that this combination exhibit catalogue / artist’s book / biblical re-telling is pretty dismal. The attempt at constructing an alternative feminist mythology is clumsy and jejune, and the project is fatally compromised by a deeply essentialist view of gender, which is embarrassing, if not downright reactionary. The visual dimension has a Blakean energy and flair, but the words therein are inexplicably rendered in a swooping, girlish cursive font; this is putatively meant to simulate the artist’s handwriting, but mainly suggests a forlorn teenage LiveJournal ca. 2002. The ubiquitous Hans Ulrich Obrist gamely contributes a “conversation,” to little benefit.

“The Laugh of the Medusa,” by Hélène Cixous, translated from the French by Keith Cohen and Paula Cohen. This foundational document of contemporary feminism, first published in L’Arc in 1975, retains its highly distinctive force and free-wheeling élan. It is a remarkable essay: angry, funny, hortatory, conceptually ambitious but with an open, improvisatory feel. “Women must write through their bodies,” Cixous demands; “they must invent the impregnable language that will wreck partitions, classes, and rhetorics, regulations and codes.”

Draw the Curtain Close, by Thomas B. Dewey. Competent 1940s detective noir from a semi-forgotten purveyor of this kind of pulp. What is interesting here is how the standard tropes of the genre — the lone-wolf private eye, the seductive femme — are executed, not clumsily, but without the cruel edge of a Dashiell Hammett or the poetry of a Raymond Chandler. The result is thin; you feel the ghostly undertow of better, more original writers, and the result is vaguely dissatisfying.

The Second Curtain, by Roy Fuller. Strange and unclassifiable British crime novel from 1953; feels like it could be from 1853. The story concerns a down-at-heels writer who is drawn into a convoluted roundelay of mistaken identity and violence upon the unexpected death of a childhood friend. It has the particular colorless anomie of a postwar London still recovering from the deprivations of the war; there is a lot of eating in grimy cafes and cigarette smoking and watery tea. A long set piece at a disastrous, drunken cocktail party is particularly well handled.

Dangerous Fictions: The Fear of Fantasy and the Invention of Reality, by Lyta Gold. Smart, light-footed analysis of the intersection of the political and the artistic, ranging from book banning to cancel culture. Gold’s special gift is to engage in some deeply complex issues about the purpose of art and the role of the didactic with a quick, slangy savvy that belies a sophisticated understanding of cultural dynamics. Gold is, in her way, a Marxist—she understands cultural artifacts as products of alienated labor—she is also an action movie and video game fan. In this and in other ways, she is an emblematic millennial. Her central idea, to my mind, is strangely consonant with a perspective outlined by Claire Dederer in last year’s book Monsters, which holds that choices made within the narrow channel of consumer culture are by definition disqualified from being legitimately political. So there.

Selected Poems of Fulke Greville, edited by Thom Gunn. Greville is the latest object of my readerly obsession, a peer of Sir Philip Sidney who wrote knotty, elegant sonnets that are both intellectually intricate and wracked by desire — an irresistible combination. The late Gunn’s affinity for Greville — these weird antique 16th-century British poets are always being re-discovered and taken up by some passionate contemporary advocate or another — serves itself as a resounding endorsement. The peculiar density of Greville’s language and diction is so intense and opaque that even Gunn is at times unable to parse its workings to his complete satisfaction.

The Intellectual Origins of the English Revolution, by Christopher Hill. The historians in my ambit universally concur in calling this 1965 book “a classic,” and it goes on my growing shelf of Marxist histories. I expect that the opaque vicissitudes of contemporary historiography have been in operation upon its reputation. It strikes me as solid, workmanlike research; I have a bit of a hard time seeing the Marxism in it, but that no doubt redounds to my own shortcomings. My fascination with the literature of the period — the 17th century, not the 1960s — is by now well documented, here and elsewhere.

The Looking-Glass War, by John Le Carré. First published in 1965, this bleak and airless spy thriller was the immediate successor to instant classic The Spy Who Came In From the Cold, which made its author famous. The novel is rebarbative and cynical; it details a doomed and hapless infiltration mission executed by a badly unprepared and ill-trained emigre spy, who is promptly abandoned to capture, torture, and death by his overseers when the mission goes awry. The effectors of this betrayal are George Smiley and the mysterious man code-named Control, who of course go on to blossom into the central characters of the subsequent Smiley novels — some of the greatest spy fiction books of all time, as well as objects of Lindgrenian near-obsession.

Reading these books out of sequence is a mistake. At the time of The Looking-Glass War Le Carre had not yet figured out how he wanted Smiley and Control to read, and they come across as petty and churlish. This is disorienting to a reader backtracking to this after the gravid majesty — the “miasmic gloom,” as one critic put it — of the Karla trilogy. In the later books the machinations of Smiley’s mind and of Control’s obsessiveness accrue, through a masterly accumulation of capacious detail, a subtlety and power that is unmatched in the genre.

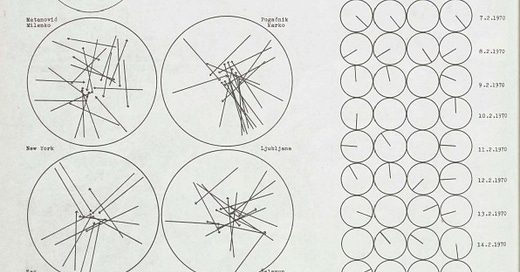

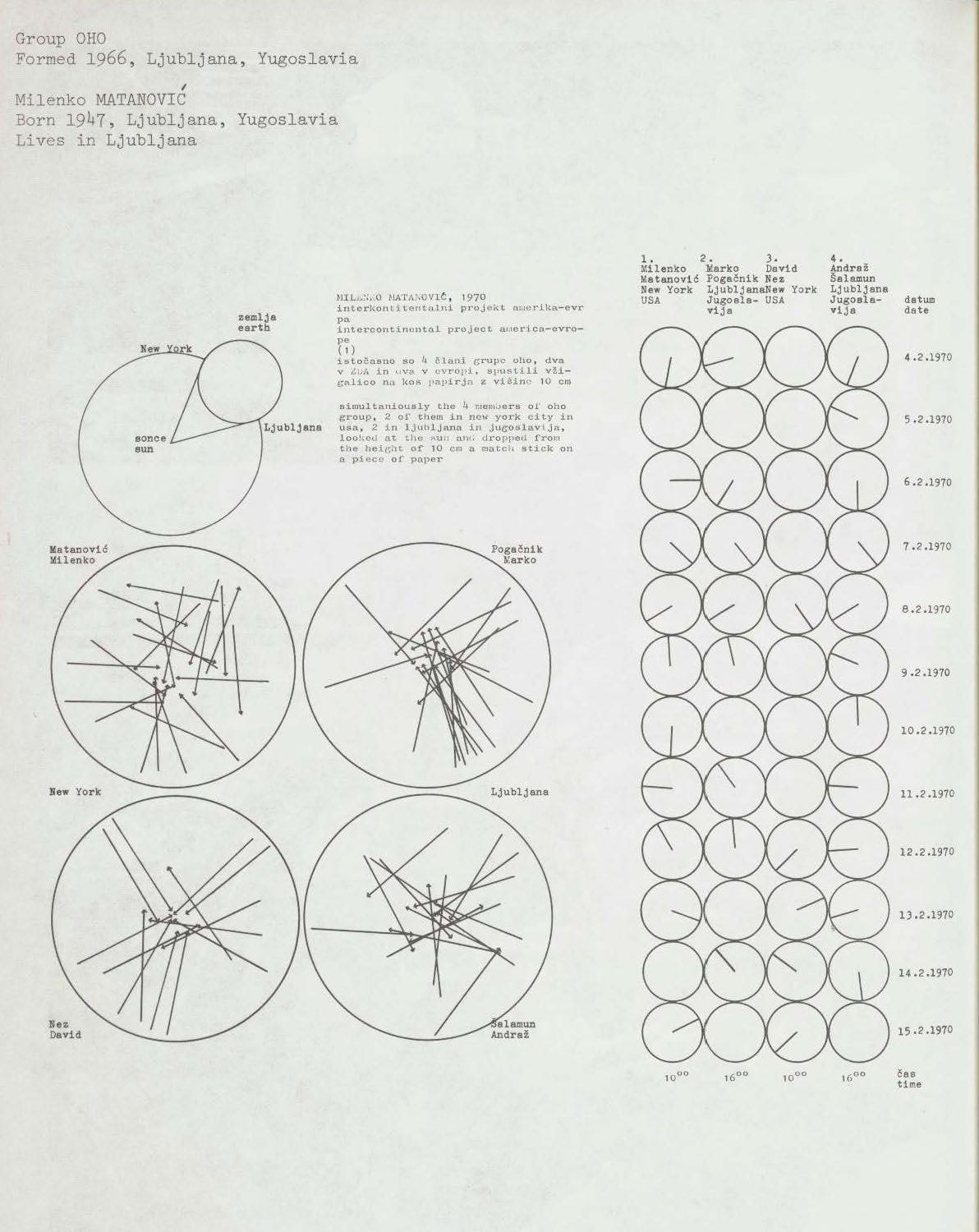

Information, edited by Kynaston L. McShine; The Xerox Book, edited by Seth Siegelaub and John W. Wendler. Two foundational documents of conceptual art, both encountered in digital versions, both difficult and endlessly fascinating. The first is the catalogue for the groundbreaking exhibit at MoMA in 1970. The book, which appears to have been typewritten, with photocopied black-and-white illustrations, is a dizzying salmagundi of manifestos, sets of instructions, happenings, recordings, jeux d’esprit, concretist prose, formulas, propaedeutica, bibliographies, diagrams, collages, detournements, and other wild and unruly artefacts of that wild and unruly time. “‘Masterpieces,’” wrote Joseph Kosuth, in a representative entry, “imply ‘heroes’ and I believe in neither”; and this sense of communitarian and anti-hierarchical energy permeates the whole movement, along with a spirit of utopian whimsy and anything-goes inventiveness. I have barely embarked on my journey into this strange and nearly forgotten school of artistic practice, fuelled so far by the memory of a transformative experience at the Whitney’s On Kawara retrospective of 2015 and a glancing encounter with the ideas and writings of Joseph Beuys. A small facet of this appeal: how does the historiography of such events work? Did the people who went to MoMA during that hot summer of 1970 know they were witnessing a historically important event? Would we, if we attended one now? Would we be able to recognize it as such? Do such things even still exist?

The Xerox Book, likewise, was a photocopied packet of philosophical investigations by the seven canonical figures of conceptual art; one thousand copies were printed in the September 1968 and distributed through readings, bookstores, magazine shops, galleries, and mail order. One of them eventually ended up in the archives of the School of Visual Arts. The project transfers to digital viewing surprisingly well; paging through it on my smartphone seems like less of a phenomenological misprision than one might think. Could such transference be a ghostly delayed reification of the original art, a kind of trans-medium functioning across time and technology? Such matters are best left in other hands …

Metaphors of Self: The Meaning of Autobiography, by James Olney. I am badly in need of some external authority to ratify the importance or irrelevance of this book (Sheila Liming, if you are reading this, call your office). As usual, I have no record or memory of how this came into my ken. Blog? Endnotes to some PDF downloaded from JSTOR? Offhand reference in a TLS review? Who knows. It is a strange book. I am both enthralled by and suspicious of it, and hence my plaintive request for adjudication. Olney’s primary premise, which he works through by analysis of seven writers from Darwin to Eliot, is that all autobiography comprises metaphor, and therefore all writing is implicitly autobiographical, working as it does to establish a correspondence between self and world.

A discussion of Olney’s book is as good a place as any to introduce a secret sub-agenda to my seemingly haphazard reading. I am going to try to write a book about literary theory, hence to be referred to as Mike’s Pretentious Unwritten Big Book of Everything. I am preparing a propaedeutic, but the MPUBBE is years, decades, off; it may indeed never appear. In the meantime it serves as something of an organizing principle and fuel for pleasant wool-gathering. If you see me waiting for the train at High Street, with an absent look and a very slight smile on my face, I am probably thinking about the MPUBBE.

“Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality,” by Gayle S. Rubin. Another classic of its kind, a celebrated essay from 1984 that codified much of what would become queer theory and sexuality studies. Much of its analysis and language — on sexual orientation as constructed rather than essential, on the legal repressions enacted on sexual subcultures — has since been absorbed so fully into mainstream thought that it is difficult to imagine or remember that these were once radical positions. This is one marker of successful work.

Rubin’s essay stands at the center of the so-called “pornography” wars of the 1980s, wherein feminists and theorists disagreed about whether pornography was inherently sexist or whether it could be part of a sex-positive feminism. [This was a historical and political moment that I find deeply fascinating.] Rubin is a proponent of the latter position, and presents a subtle and ideologically sophisticated analysis of the problem, noting among other things that “feminist rhetoric has a distressing tendency to reappear in reactionary contexts.” This stuff is all miles above my pay grade, of course, but I am faintly skeptical of her rejection of what she calls a “demon sexology,” which suggests that pornography and male-on-female rape, are, in fact connected in trans-historical ways. Near the end of her essay Rubin remarks that “in political life, it is all too easy to marginalize radicals, and to attempt to buy acceptance for a moderate position by portraying others as extremists.” That statement, surely, is perennial.

Journal of a Solitude, by May Sarton. Ambivalent about this 1973 memoir from a poet and novelist who I vaguely sense is not much read anymore. The book comprises a year’s worth of meditative diaristic entries about Sarton’s reclusive life on a farm in rural New Hampshire. Sarton was a fractious personality, one senses, depressive and quarrelsome, and the book’s fastidious tracking of her interior mental geography is both lucid and slightly wearisome. She engages glancingly with feminism along with some oblique references to her lesbianism, which gives the narrative an elusive quality. There’s an awful lot of looking at flowers and animals and the weather.

The Right to Sex: Feminism in the Twenty-First Century, by Amia Srinivasan. A deeply admirable and enjoyable book, one that brings intelligence and clarity to the muddy battlefields of contemporary feminism. Srinivasan writes for both the LRB and the New Yorker, and her voice — educated but probing, learned but not recondite — sits at the intersection of these two publications: a true prosodic sweet spot. Srinivasan teaches at Oxford, and one gets the sense that she is an outstanding professor; she has a way of asking questions that feel rhetorical but that lead into nuanced discussions. The technique suggests that the author is accompanying the reader on a shared journey of discovery.

The heart of the book, in my view, is the title essay, although I would not myself have chosen this particular phrase for the book, as it feels both vaguely icky and also inaccurate. Whatever its semiotics, it was written in response to the 2014 murder, in California, of six people by a self-described male “incel,” and the essay that followed it is a kind of coda, called “The Politics of Desire.” The latter is a stone masterpiece. It unfolds in a series of eighty-eight numbered apothegms, some of them only a sentence or two long. This is a format or technique about which I have lasting misgivings, yet rarely has it been deployed to such effective use. Its jittery, fractured affect reflects perfectly the involutions of a mind grappling with ideas of extreme ambiguity and complexity. Bullet point number 67 felt to me like a crux:

A vexed question: when is being sexually or romantically marginalized a facet of oppression, and when it is just a matter of bad luck, one of life’s small tragedies?

To the first part, I would answer “almost never”; there seems to me nothing, on the individual level, structural or reversible about asymmetries of desire. Srinivasan’s conclusion, wise but bitter, is that

There is no settling in advance on a political program that is immune to co-option, or that is guaranteed to be revolutionary rather than reformist. You can only see what happens, then plot your next move.

Under recent circumstances the statement seems to broaden in scope, and thus in meaning. But that, I fear, is another matter entirely.